Holy Hoax, Axeman

by David Jasper

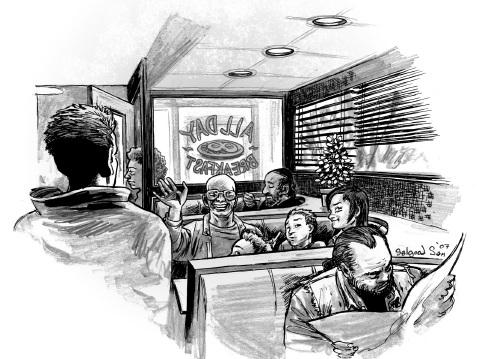

illustration by Salgood Sam

AT THE DAILY paper for which I write features, my mailbox has a lone, fat letter in it, stuffed in a company envelope. My name is scrawled on it, and when I open it up, the seal is still sticky.

Inside: a five-page letter. Actually, a letter within a letter.

The first letter is a half-page confession written by an anonymous thief. Oh, sure, one of those.

The thief wrote, among other things, that he stole from a resort-area home a laptop computer containing the second letter. “I stumbled across this story when I was downloading video games,” he wrote. “I was a meth addict up until this point, and have not used since.”

The thief was from Redmond, he said, a town to the near north of Bend, where I live. He’d pasted in the epistolary story he found. Four pages long, it was written by a woman named Julie Martin, the wife of a CEO named Bret Martin, who in 1977 had gone on a bike journey from California to Oregon.

Bret Martin stopped to camp in Cline Falls, a state roadside area near Redmond, on June 22, 1977. On the same evening, two 20ish Yale students, Terri Jentz and Shayna Weiss, were a few days into a cross-country bicycle trip. Though there was no campground, they pitched a tent on the bank of the Deschutes River. After they went to sleep, they were awakened by a pick-up truck running over their tent. The driver then climbed out of the truck and attacked them with a small hatchet.

That part of the Cline Falls story is tragically true. Poet Robert Pinsky even mentioned the bizarre incident in his poem “An Explanation of America.”

But the best artifact of that true story is the most recent: Jentz’s Strange Piece of Paradise, part mystery, part memoir, published in 2006. Now a sagacious woman in her late 40s, Jentz began revisiting Central Oregon and piecing mysteries together in 1992. Though she has no doubts anymore about the identity of her attacker, no one was ever convicted, in part because the statute of limitations for attempted murder in Oregon used to be just three years.

Was this letter I held in my hands a confession?

Sort of. Julie Martin wrote that though her husband Bret, a black-belt in Karate, was in the park that night, he was too high and drunk to intervene on Jentz’s and Weiss’s behalf.

Much to his shame, and mistaking the women for dead, he broke camp and took off on his bike on the two-lane highway heading east to Redmond. The next night, at a small-town diner in Eastern Oregon, he happened to recognize the truck and its drivers—an interesting twist since Jentz always said the man had been a lone attacker. Long story short, Bret Martin befriended the men, camped with them, karate chopped one in the trachea, killed them both and buried them in the desert.

OK, now my BS detector was ringing: That’s just way too cinematic, too pat an ending for such a frustratingly random mystery.

Yet I loved the irony: Were the story true, Bret Martin could be prosecuted for murder, yet Jentz’s attacker, if alive, could not, given the statute of limitations for attempted murder. Martin, I found, was a real, married father of two sons, and the CEO of two companies, one called Proud Warrior Productions, Inc.

Among my suspicions: “Dirk Duran” (a pseudonym Jentz created for the life-long criminal she believed tried to murder her) wrote the letter to take the heat off of himself: With the publication of Jentz’s book, national media sources had aired his real name. What’s more, the letter ended like this: “You need to let these ladies know that these men are dead, and to quit looking for the individual that attempted to kill them. … Its (sic) over.”

When I showed Duran’s mug shot to Dorothy, the receptionist who’d given the dual-letter’s deliverer an envelope, she didn’t miss a beat: She was positive the guy who had dropped off the letter was Duran.

My only role in all this: I’m a come-late-to-the-story reporter who had written about Jentz upon her book’s publication, just prior to a reading she gave here in Bend. With Duran out of jail again, Deschutes County Sheriff’s officers patrolled outside the bookstore to ensure her safety.

I’d spoken with some of her many friends here, like Boo Isaak, who was the first to drive through Cline Falls that night in 1977, and see a terrifying vision: a blood-covered Jentz running toward his truck looking like a Manson Family victim.

In the letter, Bret Martin’s wife said her husband had not known what became of the women until he read my story in May. The attack was major news in 1977, but he was a bicycle bum and didn’t follow the news. He pedaled off and, a healed man, went on to a normal life. My story inspired him to confess his crimes, except that he didn’t do any confessing. A thief had sent the letter.

Even with my burgeoning skepticism, it felt like I was being drawn further into 30 years of drama by a taut bungee chord attached to a shadowy giant. I e-mailed Terri, who was coming to town, and told her I had something weird to tell her. She left a voicemail immediately, and sent some messages via Blackberry, but before I called her back, I had to call the Martins, whose Portland number was listed, to see what role Bret Martin had in this. Did he know Duran? Had Duran or one of his meth buddies somehow robbed the Martin’s second home, in Sunriver, a nearby resort area?

Once I got him on the phone and identified myself, I hemmed and hawed, trying to tell him the story so far. “Go on,” he said. “Tell me more.”

Then he cut in, “I assume this is about Terri Jentz.”

Yipes.

Martin said he and his family were headed to Sunriver that evening, and that we should meet at the paper on Saturday morning. My colleagues warned me not to meet him alone. He was gracious when I called back, and suggested that we meet in a more public location.

Did I mention he’s supposedly a black belt?

We agreed upon Black Bear Diner, a little farther away.

“Black Belt Kills Reporter Bare-Handed at BBD.”

Little did I know then that he was at home gleefully high-fiving his sons and telling them, “Dude, he’s scared of me!”

When I walked into the diner, Ben, the paper’s music guy, and his wife, Emily, were already in a booth. I waved and loosened my collar as the hostess led me to a private dining area where Bret and Julie Martin and their sons were sitting.

“David, I wish it was a story that I’d written that was the truth,” Bret said. “I need to let you know that right up front. It’s bogus. And if you got up and left right now I wouldn’t blame you.”

“No, I’m still curious. The person who delivered it looked like Dirk Duran, and I don’t know if it was,” I replied.

“I delivered it,” he said.

“You delivered it,” I said back.

“I went in and I met your receptionist. I didn’t even have an envelope. The reason I used your guys’ envelope was I thought you’d be more apt to read it. … I’ve been in sales the last 19, 20 years. Now you look at me—and she’ll say the same thing,” he said, nodding at his wife. “She would say, ‘Why?’”

He needed to tell it chronologically. “I read your story, absolutely enjoyed the hell out of it. I immediately went and got her book, tore it apart, read it to shreds.”

“He read it in the bathtub … all of his books look like that,” Julie Martin said. “It’s pathetic.”

“Memorized it,” he said. Then he pulled out his driver’s license. “Just want to show you I’m the real. I’ve got my family (here) for a reason.”

I was recording the conversation, and a minute and 30 seconds into the meeting, I said, “Are you an aspiring screenwriter or something?”

“I’m trying, I’m trying,” he replied.

Most people I’ve told the story to said they would have walked out at this point. I did get annoyed later. But at that moment we talked and laughed. It was anti-climactic in a good way. He was rich and arrogant, and clearly accustomed to doing things his way.

And, of course, he looked nothing like Dirk Duran. Bret Martin was the picture of middle-aged health, if maybe a bit too well fed.

He offered to pay me for my time, but how do you put a price on almost being hoaxed? But I did let him buy my breakfast, and Ben and his wife’s—they joined us from the dining room. You should have seen Bret Martin’s face light up when I mentioned that Terri Jentz—a screenwriter who lives in Los Angeles—was in town that day for another reading; a coincidence, but Martin doesn’t believe in coincidences.

“No!” He clapped hands and bumped knucks with his sons. “I told you, dude, it always works out. I’m always telling these guys.” To his family, he added, “I’m at least gonna say hi, and I’m not going to be weird. That’s what I at least want you to know, is that I’m not a weirdo.”

I never did get a satisfying explanation for why he delivered the letter to me, except that Jentz’s publisher’s gatekeepers did a good job of blowing him off. I did not. Gullibility is a job hazard of being a writer of fluffy features.

I’d made plans to meet Terri Jentz for dinner that evening, and Martin asked if I’d give her a copy of the letter. I said I would. But I didn’t remember to bring it in the restaurant that night.

I was plenty embarrassed, yet I still thought she’d be interested. As I unspooled all the convolution, she said, “Give me the short version.”

I tried. She cut in, “He confessed to the Cline Falls crime. I’m surprised you haven’t gotten hundreds of confessions.”

Not exactly, I said. When I finished, she said: “It’s interesting.”

That’s it. So much for Martin’s pitch, although he did attend the reading.

She later e-mailed me: “He came over to me when I was getting out of my car and wanted to see my scar! What a nut job. He had me sign several books by scrawling my name in felt marker over the front covers, and even had me sign my picture in The Bulletin article you wrote. A nut job, but harmless, I think. His wife seemed quite normal, but I guess I could have her all wrong.

“As you know, in this culture, any degree of ‘celebrity’ brings out the cult types—and so far I haven’t had any of that behavior coming at me—until this week. Both in Hood River and particularly in Bend I had some obsessed fantypes pursuing me. One woman in Bend leaned into me at my signing table and with huge popping eyes, said, ‘I am obsessed with you. I’m a nut but I know from reading your book that you’re a nut too, so you can understand me.’”

The sad thing about Bret Martin is his blind ambition. Even knowing that Jentz is a screenwriter, he somehow thought she’d surrender her story, one she recounts in over 500 pages in her book, and sell the movie rights to him. Possible filming locations were already being scouted on her behalf.

It was naïve and arrogant, yet he was moved by her book, having survived being hit by a drunk driver when he was young.

“It’d be worth a cold beer or a pop to say, ‘Hey, I know what you went through. I never realized until I read your book how so many other people were affected.’ My father quit his job as a realtor and stayed home for a full year with me.”

Still, that arrogance: “Even if there is a movie being made, or a screenplay, there’s material that I’ve got here that they’ve got to add to it, I truly believe,” he said.

And then there was this: “If that happened to me, I’d want to know who did it … and she has a need for it. She wants closure. That’s why I’m hoping like hell, if I can get her to calm down and not be angry at me, that I could say, ‘Look, let’s go for some fake closure. It’s almost as good.’”

Before I could escape our breakfast meeting, my would-be-hoaxer bear-hugged me and promised he’d have my family down to the mansion for a cookout sometime.

Talk about fake closure.

David Jasper lives in Bend, Oregon, with his wife and three young daughters. He rides his bicycle only when commuting.

Hi,

I was born and raised in Redmond. I moved to K-Falls at age 21 in 1975. Then to Southern Cal in March 1977. My mom and dad remained there. Mom died in 2000 and dad in 2011 at age 95. I know many of the names in this vivid book, but not all. I did here about the attack when it happened. And I knew Terry Abbott personally, as I lived 4 doors to the south of his childhood home until I was 18.

I would really like to know the real name of “Dirk Duran” to see if I know him. How can I find this out?

I realize I’m late to the party, but I only learned about this book less than a year ago. I just read it finally, this week.

Thanks,

K.S.

Dick Damm

http://imgur.com/a/rFGul

Thats him

Pingback:5 Real Life Wilderness Horror Stories | girl on rock

“I’d spoken with some of her many friends here, like Boo Isaak, who was the first to drive through Cline Falls that night in 1977”

Boo Isaak is a woman. She features prominently in Jentz’s book. I imagine Jasper was working from an old article/notes here and doesn’t recall the conversation or conversations.