Under the Covers

Jonathan Franzen Will Never Write a Novel in This Town Again

by Carla Costa

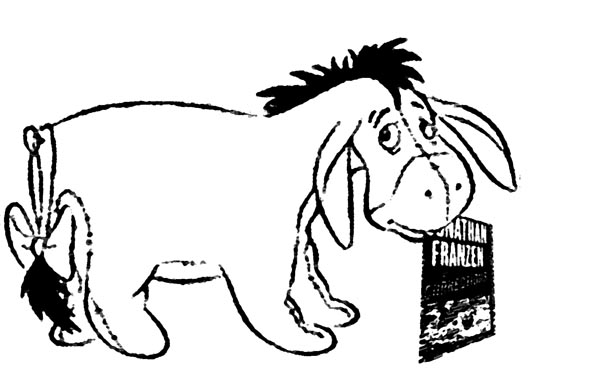

illustration by Nicole Neditch

IN THE YEARS since the publication of his last novel, The Corrections (2001), Jonathan Franzen has talked so much shit about the American novel that he may never write one again.

Franzen just released his second collection of autobiographical essays, The Discomfort Zone, and shows no sign of working on a new novel. He has, however, written letters to writers who criticize his work and the opinions put forth in his now-infamous 2002 essay about reading William Gaddis’ The Recognitions, “Mr. Difficult.” In his defense, you’d think that in four years writers would have found something better to talk about than an piece by a nerd who grew up to write philosophical essays on birding for The New Yorker.

Unfortunately for Franzen, Ben Marcus reprised the chorus of sighs spurred by Franzen’s essay with a tiresome diatribe of his own entitled “Why Experimental Fiction Threatens to Destroy Publishing, Jonathan Franzen, and Life as We Know It.”1 Ben Marcus is a funny guy.

Simultaneously, a new issue of n+1 (Fall 2005) hit newsstands, featuring an essay from New Republic senior editor and literary critic James Wood, with his own take on the State of the American Novel. It includes some notes on Wood’s own complicated relationship with Franzen as not only a critic but a respectful reader of Franzen’s novels. The result was the appearance of a letter from Franzen in n+1’s Spring 2006 issue (which includes a lot of exclamation points), an attempt to defend himself from misinterpretation and call Wood to task on his own (supposedly) contradictory statements. It’s followed by an as-yet-unanswered letter from Wood in an issue that attempts to review the State of American Writing Today. The more Franzen writes nonfiction, the more difficult it is to keep from finding fault with the guy. Perhaps this is because he does such a great job of pointing out his personal deficiencies with his Eeyore essay-writing style. Poor Franzen can’t catch a break, but why can’t misguided editors, writers and critics stop trying to peg down the American Novel as an either/or proposition (good/bad, experimental/mainstream, progressive/staid)?

A rudimentary question still begs to be answered: Why should we care what Jonathan Franzen, Ben Marcus, James Wood, and the editors of n+1 (among many others) see as the State of the American Novel? Because they’re novelists? Because they’re editors? Because they’re academics?

None of these writers offer anything more than analytical opinion. In this context, they’re all critics, and although their expertise is valuable, it doesn’t necessarily intersect with what true lovers of literature (and other readers) take home. It does not account for individual tastes or for PR-machine hype; it does not account for the ever-surprising nature of book sales. Instead, it extends the notion that readership can be pinned, mounted and traded as a commodity, yet none of these parties seems to really believe that an audience can still make a novel. In their criticisms of Franzen, none of these writers really broach the intricacies of alienating readers, which is exactly what Franzen aimed to do with his “Mr. Difficult” essay. Also, they appear to exist in a world where the industry of publishing has little to do with what’s written and the way it’s written. This world is, of course, make-believe, and not in some post-modern, metaphysical way.

Mr. Difficult

Franzen’s “Mr. Difficult” reads like a neurotic novelist posing as a reader in order to assess whether or not complex writing (known as experimental in some circles) will make a book more or less sellable or respected. He must have been merely curious about the matter, since it doesn’t seem like Franzen has any intention of using the feedback to write a new novel. At least, not that he’s told us, anyway.

With his latest nonfiction book, Franzen is doing just what I would do in his position: dodging the unbearable pain of writing a follow-up to a book like The Corrections, which stands not only as his most popular and best-selling work to date, but also (thanks to the Oprah controversy surrounding it) the revelation of his desire to be, at once, a cult writer and a bestseller—or to be loved, but only by the readers he likes. The fact that such a goal is made unattainable by the structure of the publishing and marketing industries could be the one point on which Franzen and his critics agree. It’s old news, after all.2 If only they would just talk about it, but to do so would mean admitting that some of Franzen’s critics long for the same unattainable cult/mainstream status.

Few writers have successfully walked the line between cult status and industry success (at least in their lifetimes). Those who have followed a similar tack of getting out of bed and out the door before the follow-up novel wakes up and demands to be written. Take, for example, one of the other Jonathans. Since his bestseller, The Fortress of Solitude, Jonathan Lethem released a collection of autobiographical essays, The Disappointment Artist, followed by one, and soon another, collection of short stories. The short stories are entertaining, but The Disappointment Artist is for suckers, people who have the exact same aesthetic taste and the same hobbies/interests as Lethem but are too lazy or disinterested to write about them at length and call it essays. If you aren’t in that camp, you’ll find yourself left out of the world Lethem makes for his readers. This may not be so bad for Lethem, since the time away from novels will shake many of his mainstream fans, separating the wheat from the chaff, and ensuring that when he does write another novel, it will be for those cult readers who stuck with him. He will be loved, but only by the readers he likes.

How to Be Alone

The difference between Franzen and Lethem seems to be that the more Lethem writes about himself, the more his devoted fans admire him. The more Franzen writes about himself, the easier it becomes to dislike him, to purposefully misinterpret him, to make fun of him and use him as a target for a game of literary darts. Franzen is, as is revealed in The Discomfort Zone, a well-meaning kid who’s too cool to roll with the losers and too much of a loser to roll with the cool kids. A cartoon by Patricia Storms, The Amazing Adventures of Lethem & Chabon,3 in which Jonathan Lethem and Michael Chabon save a middle-aged man from disinterest in literature with their “action-packed novels about male-bonding and self-discovery,” also features a telling frame in which Franzen begs Lethem and Chabon to let him join their literary superhero dynasty:

Franzen: But I can appeal to the macho mind, too! Why, I even wrote an essay about comics in The New Yorker!

Chabon: You mean that drek about Peanuts?

Lethem: You think that’s gonna put you in our league? You’re hilarious, Franzen!

Chabon: Face it, Franzie, your writing is too soft. You’ll never play with the big boys.

Lethem: Should have kissed Oprah’s ass when you had the chance, girlie-man!

I, for one, like Peanuts, but I long for the days when Franzen was rewriting the literary mystery (The Twenty-Seventh City, Strong Motion), and instead of pouring himself into a pity-party collection of essays, was pouring himself into the protagonist of his next novel.

It is, essentially, impossible to get and keep all readers. It is, essentially, impossible to dictate what readers want, and especially what they want from a novel. The best novelists do not define an audience and write their way into a readership. The readership comes to them. To attempt to describe The State of the American Novel and make demands for its betterment without acknowledging that one’s opinions are only as valuable as those of their readers is not only foolish, it’s the kind of thing that destroys careers.

1 Harper’s Magazine, October 2005

2 See: Theodor Adorno’s “Culture Industry Re- considered” from The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture (Routledge, 2001).

3 stormsillustration.com/L&C-1.html

Carla Costa is a bookseller who continues to recommend Jonathan Franzen’s Strong Motion, thinks Ben Marcus’ The Age of Wire and String is brilliant, reads every issue of n+1, and wishes Lethem and Chabon really were superheroes so she could giggle at their man-bits in tights. Send your reading recommendations to carla@kitchensinkmag.com.