Hey Bartender!

Rebel Yell

by Lee Skirboll

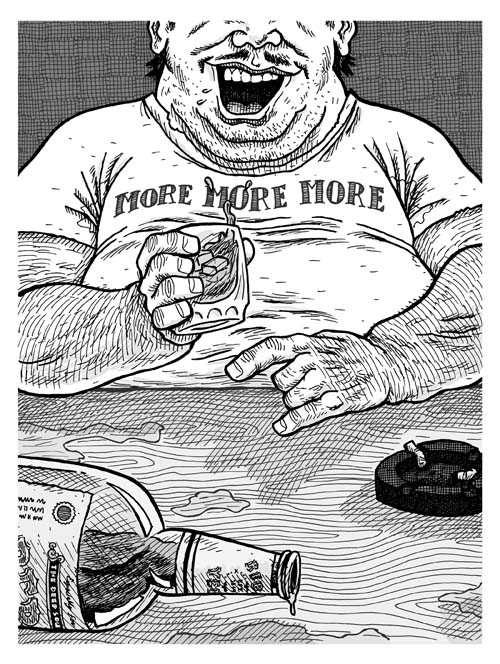

illustration by Jamie Tanner

“HEY!” BUBBY SAYS, hoisting his rubbery bulk onto a barstool. “What does a fag Chinaman order for lunch?”

I worry about our barstools, their age and disrepair. Having somebody as disgusting and bulky as Bubby heaving himself on and off them daily must surely put undue strain on their rusty supports. We’re an accident waiting to happen, I’m sure of it.

Bubby waits with the infinite patience of a seasoned pest for me to cue his punch line, and I will do almost anything not to comply.

His jokes pose a typical problem for me as a bartender and a citizen of the universe at large. These kind of jokes are never funny and are always racist and obnoxious, but as a bartender I am expected to at least listen to them, if not repeat my own versions on demand. At some point I began to worry about the effects of listening passively to these jokes, what their cumulative effect may have been on my psyche, like poor Alex in A Clockwork Orange, eyes pried open to the violence. Yet for me not to hear Bubby’s joke I will have to do some extra work, and extra work is the scourge of any self-respecting bartender, which effectively doubles my irritation. I have boiled it down to the following options:

1) Tell Bubby I do not want to hear his joke. I’ve tried this tactic before, with Bubby and the countless others who enjoy this sort of repartee: “If you don’t mind I’d rather not hear your racist or offensive joke, no reflection on you or your family, however suspicious or damaged your moral base may be. Thanks anyway for your desire to share.” Unfortunately, the response to this is almost certain to be: “What are you? Some kind of (fill in the blank) lover?” Or, “You must be sensitive or something,” meaning I must be some kind of effeminate, communist, politically correct, tree-hugging, Greenpeace commie bastard hippie Jew no fun party killing thought police. Plus I will usually hear the joke anyway, making the whole exchange moot.

2) Walking away. I can usually feign important business that must take me abruptly to another part of the bar. Problem is, I will most certainly hear the joke when I return, sometimes hours later.

3) Running away. I think about it. Just throwing down my bar rag and fleeing wildly down the street, hands waving, shrieking, the whole thing.

4) Jabbing a fork in Bubby’s throat. Possibly the most attractive option.

It is inevitable that with somebody like Bubby—who is a sociopath, i.e., completely unaware of his effect in a social setting, who has no embarrassment or self-reflection of the discomfort he causes others—that I will just have to tough it out. So, like a man in a hurricane, I try to steel myself against the oncoming joke.

“What does the fag Chinaman order for lunch?” Bubby asks again, and I wipe the bar in a way I’ve perfected that I hope expresses weary, disinterested neutrality.

“Cream of some young guy,” he says, then he giggles.

I realize too late that I’ve heard this joke before, probably several times from Bubby himself, and have failed to retain it for future reference, for exactly a moment like this, when I could’ve beat him to the punch line and per- haps diffused the joke. Sadly, one of my many failings as a bartender is that I either refuse or am unable to remember jokes. I believe this is a defense mechanism, that jokes are indeed toxic. The phrase “killing joke” pops into my head, based on Monty Python’s famous skit where a joke is so funny, the hearer laughs himself into convulsions and dies; then to David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, which also plays on the idea of an “entertainment” so potent it kills the observer; then to the mediocre post-punk band Killing Joke, who took the name for unknown reasons and managed somehow to suck the fun out of it. To my horror, an errant chuckle has escaped my lips. In all my postmodern referencing I’ve managed to find Bubby’s joke funny on a private level (I try to cover the chuckle with coughs—we would never want to give Bubby the impression that we’re laughing at one of his jokes), funny because I believe Bubby is, like over 50 percent of all the male customers in this bar, latently homosexual, and confusion and tension in this area have driven him, along with the others, to near psychotic breaks with reality. This of course is humorous to me.

My mirth is short-lived, as Bubby has seized upon the slightly upturned corners of my mouth as a sign of entry, of camaraderie, and slaps his palm upon the bar and shouts, “Rebel Yell, my good man,” and suddenly rusty gears of deeper referencing start grinding away in my mind.

Bubby drinks Rebel Yell, a brand of whiskey we only stock for him. Our bar, a true neigh- borhood dive, says that no matter what kind of person you are, if you have some kind of weird, back-woods, Deliverance-type sour mash whisky you want to drink, we will stock it, providing you will agree to drink enough of it to make it worth our while. Long ago, Bubby proved he was at least worth his prodigious weight in Rebel Yell.

I fill a rocks glass with ice and scan the bottles for the Rebel Yell. As I do, against my will or control, the Billy Idol song “Rebel Yell” leaks into my consciousness and attempts to take root. I panic. Under no circumstances do I want this song in my head, yet I fear it may be more powerful than I. Again I blame Bubby, who not only brought his joke and its inherent references to my bar, but is himself a carrier, a carrier of a potent brew of obnoxiousness and postmodern referencing, a social pollution of the worst stripe.

This adds to my paranoia about the toxic workplace and is distressing on an ever-increasing system of unhealthy hierarchical levels which go something like this: Bubby; barstool; joke; killing joke, Monty Python, Clockwork Orange; Rebel Yell; Deliverance (Ned Beatty violated); “Rebel Yell” Billy Idol repugnant song; Billy Idol MTV lip curling, fist pumping; collapse of music and the erosion of all we once knew was good and just.

“Rebel Yell” is indeed a horrible song of the very lowest musical value and represents approximately 150 things I hated about the music industry in the ’80s, including how Billy Idol, the singer of the song, somehow flipped from being an authentic critic of popular culture to an genuine parody of himself and the object of the same criticism. For Idol to eventually produce a song as grossly corporate, smugly commercial and musically repugnant as “Rebel Yell” makes me stop and sadly reconsider the values I held as a youth.

Perhaps worse, thanks to MTV (back in the day), whenever I hear the song “Rebel Yell,” triggered by Bubby’s giggling drink order, I can’t help but also see Billy Idol’s stupid, shit-eating grin in my mind’s eye, gumming out the words to “Rebel Yell,” pumping his fists in the air like every Bud-swilling, MTV-watching frat boy who would have certainly wanted to beat Billy Idol up if he had seen him walking down the street in his punk-rock days. While Bubby’s joke and its accompanying references and associations have caused me to worry about my polluted workplace, the addition of the Billy Idol audio and visual components are perhaps truer cause for alarm.

Many have criticized MTV over the years for purportedly extracting our imaginations from the music-listening equation. As one of MTV’s own cunningly self-depreciating promos once said, thanks MTV for replacing the pictures in my head with paid advertisements and corporate marketing messages. This all supposes that music used to be a form of “pure” listening removed from any other activity. Yet listening seems to crave a visual complement. The big- gest disservice MTV may have provided was to flip the ratio, where audio became background to the visual, perhaps never to return. But give MTV credit (or demerit) that even I, a Billy Idol detractor, had sat through the “Rebel Yell” video enough times for his harmful image to be burnt into my once-precious rods and cones. So not only do I have Bubby leering and slurping his whiskey before me, basking in the greasy afterglow of his nasty joke, but Billy Idol leering there as well, his wet lips and white spiky fright wig superimposed in the same ultimately bad space.

I pour Bubby a generous shot of the mash, perhaps imagining it is for me. The ice crackles to the opening bars of “Rebel Yell,” and I wonder just how much space in our brains and on our barstools we are willing to cede to obnoxiousness. It is not only jokes that emit fumes, but their repugnant human carriers who secrete a type of social pollution. Like Bubby, like Billy Idol, they invariably reference a deeper media saturation of equally toxic audio and video, adding to its potency. Like the slow leak of asbestos from our bar’s insulation, it is undoubtedly killing us all.

To read more of Lee Skirboll’s Bartender Series, visit kitchensinkmag.com.

Staff writer Lee Skirboll would like you to imagine “Dueling Banjos” playing in the background of this piece.