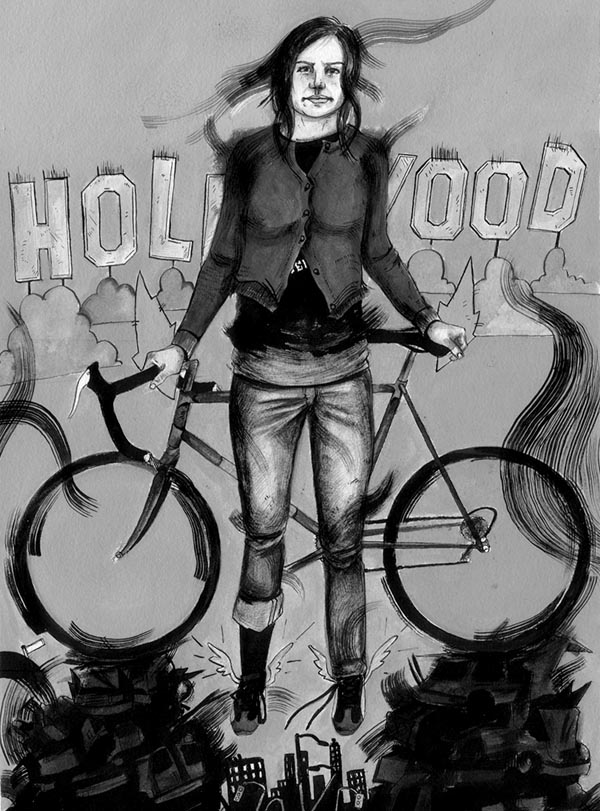

Two-Wheelin’ in Tinseltown

On Cars, Class, the Planet, the System and Riding a Bike in L.A.

by Jessica Hoffmann

illustration by Chris Lane

IT’S ANY GIVEN HOUR, any given day in Los Angeles, and there’s a long line of shiny SUVs streaming out onto 3rd Street from the Grove, a mall designed to evoke a city-plaza feel with its cobblestone outdoor walkway and quaint trolley, although in fact it faces inward, toward the actual city it’s in, tall white walls decorated with advertisements for the stores on the other side. You can see shopping bags with sturdy twine handles through the streaming SUVs’ rear windows, plastic Coffee Bean cups and cell phones in their drivers’ manicured hands. They are streaming out onto a public road from a private one, making easy lefts three or four at a time.

I want to say: This image epitomizes L.A.

I want to say: Don’t you people know there’s a fucking war going on?

But then, I don’t want to say those things. But I do.

Fuck Westwood, and Hollywood, Too

It’s a different day in L.A., not any given but a specific one in the spring. I worked all day in Venice and then hopped on my bike to head to a screening of some Brothers Quay films in Beverly Hills.

I’m easy in a tree-lined bike lane from the beach all the way to Westwood.

But then Westwood.

Wilshire Boulevard is eight lanes of fast, impatient traffic with no shoulder or parking lane, the rightmost lane of cars speeding inches from the curb. So I take the otherwise empty sidewalk. But then the sidewalk abruptly ends and I have to choose between backtracking for blocks or waiting for a pause in the rushing traffic to jump into that right lane and then ride my fastest (which ain’t fast) with a stream of rush-hour commuters honking behind me. Fuck ’em, I decide, and jump in. But, quickly remembering I’m much more vulnerable to their apparent “fuck her” than they are to my “fuck ’em,” I jump back onto the sidewalk as soon as I see another one. And then that one ends, abruptly, this time at the bottom of a long, steep grade. No way am I gonna get in that rushing right lane up this thing. There’s finally a street branching off Wilshire, so I take it, ready to wind my way east on some side streets—which turn out to be smooth and quiet but also windy and looping back and back on themselves, and now I’m lost in some hills above Westwood, late.

And angry—at the simple fact of an eight-lane street with not even a sliver of room for a cyclist during rush hour. At the too-many people rushing relentlessly forward there, alone in their massive vehicles. At the stupid waste of the lawns I’m riding by in the middle of a desert pretending it’s not one. At—I’m angry at so many things that when a woman in a hulking gold Lexus comes careening onto the street without noticing me in her path, this hardcore feminist head of mine thinks “fucking dumb blonde SUV bitch.”

But maybe I have no one to blame but myself. Because who the fuck rides a bike in L.A., right? This is the City of the Car I’m trying to two-wheel across. A city where I’ve heard more than one peak-oil-worrying, capitalism-smashing radical (myself included) explain that she still owns a car because “it’s a necessity here,” where a ’30s experiment with socialism in the desert envisioned one car per family as part of its utopian dream. This is a city of sprawl, a city famous for its elaborate freeway system and the long lost red-car rails that were paved over to make way for it.

Some days I think no scene better symbolizes L.A. than the near-constant stream of gleaming SUVs, shopping bags visible in their back windows, coming out of the Grove.

But really, I remind myself, that image just symbolizes one story of L.A. It just happens to be the one that predominates.

Except, Actually, I Heart Hollywood

There’s a serious class dimension to the story of L.A. as a city of cars and vanity and materialism. The everyone-drives-in-L.A. story elides the realities of the many poor and working-class folks who have been moving via public transit and bikes and their feet here for decades. It’s a story of a town of rich, beautiful individuals zooming about in shiny cars, created and disseminated by Hollywood—that’s metonomyic Hollywood, mind you, as opposed to the actual Hollywood that I live in, which for generations has been inhabited primarily by working-class immigrants from various parts of the world and which I’ve heard is the most linguistically diverse neighborhood in the country. Yet the L.A. fable is a fairly accurate story of a certain privileged and insulated population in this city, a chunk of which repeatedly projects it on big screens.

The literature of car culture, cinematic and otherwise, casts the car as both flashy and liberatory. The car serves as both a status symbol and a means of escape in countless road-trip and getaway narratives. Even for writers exploring marginalized social positions (On the Road, Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car”), the car represents an escape from conformity, from limited possibilities. While it’s easy to see why movement is associated with freedom, why so much love for the individualistic MO of the auto?

The difference between individualism and individuality is obscured in super-consumer cultures. Can’t we be nonconformist and also community-minded? Liberated but not at the expense of others and the places we all share? Individualism casts us all as in competition with each other, and this particularly capitalist construction is deeply tied to American—and Angeleno—car culture.

Thinking Outside the Box-on-Wheels

Biking in L.A. is an opportunity not only to reduce emissions, get exercise, and all that good stuff, but also to break out of the isolation and insulation that driving a car here entails and perpetuates—and that I think is directly related to de facto segregation in this city, and the lack of meaningful cross-class contact that makes it possible for people to displace, under-pay, pollute the neighborhoods of, and otherwise exploit people whose lives they have failed to imagine.

You don’t see what I’m calling segregation when you move from one point to another in your air-conditioned, hermetically sealed car. If you move through L.A. exclusively via auto- mobile—especially if you are a person whose skin and class privilege allows you to work and socialize exclusively with people who are “like” you, if you choose—the city becomes a composite of points where you choose to park and get out. The spaces between are a blur on the other side of glass. It’s L.A. as a constellation of selected destinations, with partially or unimagined blank spots in between.

Except, of course: People live in those blank spots. I live here. There is nothing like blankness, here, at all. There is just, for some, the unseen.

On a bike or a bus or on foot, one is inescapably engaged with different people, different neighborhoods—the small sensory particulars of them, their sounds and smells and qualities of light and of life. When I move through this city, as I increasingly do, on my bike, I’m talking to people, I’m seeing the neighborhoods I move through. I’m noticing big and seemingly small stuff all along the way.

Discussing how resource impoverishment is connected to a poverty of choices, author/activist Amber Hollibaugh writes about how you can’t imagine your way out of a world that has no map, how “there is no map for an invisible world, no path out of a closed system.”

While Hollibaugh speaks of the maplessness of the poor, I want to suggest that in this city, with its extreme wealth gap, in some senses it’s the so-called have-nots who are moving through the world in a way that’s not only more sustainable but that also affords them a more complete view of the spaces they’re moving through. The mapless, in this case, are the ones who can’t imagine a way out of a system that poisons everyone in it because part of how they benefit from it is blindness.

Let me revisit that list of things for which L.A.’s famous. In addition to cars and vain materialism, there’s that other bit of the sprawl story: development struggles. From Chavez Ravine to the South Central Farm, individual profit/ power interests’ trumping social and environmental values is part of the L.A. story. And, as is too often the case historically, the folks with the power to create the authoritative maps are the ones who can’t see what they’re mapping, whose views are literally circumscribed by the ways they’re moving through their city, their lives, our world.

Hitting the Glide

It’s another day in L.A., this time early morning. It’s not hot yet and the air is clear and I’m gliding downhill. At 12th and Rimpau, I think about Lisa Anne Auerbach, whom I know only via a recent Los Angeles Times piece on bicycle commuting, which described a sweater she made that says “On My Bike Los Angeles Is Mine.”

Yeah, I think as I turn onto 12th, on my bike L.A. is mine.

Or no, I think as I turn again and pick up speed down a bigger hill, it’s not that it’s mine, exactly, it’s that when I ride, I’m really in the city and of it. When I’m moving through L.A. on a bike, this city of sprawl and alienation and a crazy wealth gap is accessible and rich and beautiful in all sorts of non-monetary, non-manicured ways. On my bike, it’s not that L.A.’s mine, but that it and I are complicatedly engaged—and what I’m engaged with is not the notoriously alienating celluloid city but the L.A. I’ve spent most of my life in, the L.A. I love—one of the most diverse cities in the world, where you can spend hours outside daily all year long, where the mood shifts every few blocks, where people are walking—and talking to strangers and eating mangos on corners and planting side by side in community gardens and… and… and…

…And I really don’t want to ask some dumb SUV bitch if she knows there’s a war going on, don’t want to demonize her or anybody. Because I don’t really think anybody’s a demon. I think we’re all products of a system that hurts all of us and the earth we’re standing on, and that both privilege and lack within that system, in their different ways, make it hard to map a way out. And I know that this mood, this angle, is hard to hold onto. Finding a peaceful side street helps. So does pedaling so hard I start to giggle at my strength and speed, sometimes. Other times, I get the mood back by reminding myself that I don’t have to get there asap, that I live in a city where many streets are awesome with the scent of jasmine, which brings back scenes of old friends and other L.A. phases and neighborhoods. And tonight I can just inhale that—I can just glide.

Jessica thinks you should know: There’s quite a vibrant bike culture in L.A. (check out cicle.org and bicyclekitchen.com). And she wants to say hi to Nick-the-house-manager-at-Redcat, who opens the special door for her to park her bike while she watches strange films.