Tom Waits Ruined My Life

by Stefanie Kalem

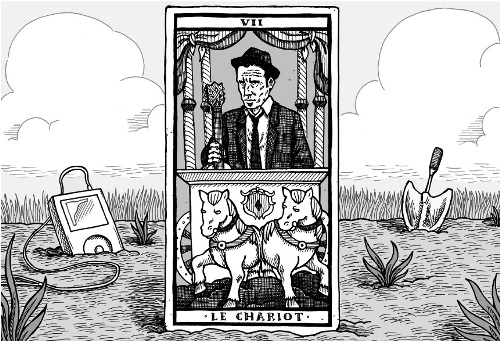

illustration by Jamie Tanner

I WAS skulking around Zoli’s yard in broad daylight, hooked gardening tool pressed against my palm, musing on the nickname “The Poplar Hunter.” Steve “The Crocodile Hunter” Irwin had just died, but this was only my first day working in the yard. I hadn’t devoted my life to landscaping—I didn’t even know the name of the tool in my hand. However, pulling out poplar sprouts by their roots had thus far proven to be my most successful task that day; wheelbarrowing bricks had hurt my back, as had digging small trenches in the dirt beneath Zoli’s new fence. When he asked me to make one furl out three inches on either side and slant down, so the potentially wood-rotting rains would have an additional place to go, I asked him for his opinion of my slope so many times that, when he finally told me “I think you’re done,” he was most certainly just letting me off the hook for both of our sakes.

But the poplar-pulling thing was working out; I ground my barely tanned knees deep into the coffee-brown dirt, adjusted my borrowed back brace, and started thinking about the nickname/superhero identity “Poplar Pullr” (after Liftr Pullr, the predecessor to the band the Hold Steady) as my tool dug under the earth again. Zoli’s iPod coughed up Tom Waits, and, as I examined my freshly yanked pelt for signs of being ivy, not poplar, I found myself singing along:

Never saw the morning till I stayed up all

night.

Never saw the sunshine till you turned out the

light

Never saw my hometown till I stayed away too

long

Never heard the melody, till I needed a song.

I stopped myself. Stood up.

“What bullshit,” I said, to no one in particular.

“That’s ivy,” said Zoli. “But it’s cool. I don’t like ivy, either.”

I like Zoli—he’s my friend’s housemate and also her landlord, and he owns this sweet piece of property in the Glenview neighborhood. By next summer there should be a creek and a pond and a hot tub in his backyard, and I’ll be proud to say I was a part of the yard’s renovation. My friend forwarded Zoli my desperate plea for paid work earlier this week, and he responded with an offer of $15 an hour for seriously unskilled landscaping labor.

So yeah, he’s cool. I can’t even begrudge him Tom Waits on his iPod. For one thing, I’m the one who knows all the words to “San Diego Serenade,” and I’m an honest sort—hardpressed to front to my friends, strangers and myself. Compulsively so, even in my youngest years. F’rinstance, I used to hate Three’s Company. “How could you,” I’ve been asked, “deplore this sitcom of all sitcoms, this boilerplate of ’70s wackiness?” Easy. Every single episode of that show revolved around dishonesty, whether it was outright lying or just misunderstandings that could have been easily cleared up with a direct question, followed up by a truthful response.

That was when I was in elementary school, shortly before the release of John Waite’s “Missing You,” a song that would strangely haunt my Tom Waits obsession. Let me explain—I came to love Tom Waits while living in Central Florida, and upon mentioning him to my office coworkers or family, I’d invariably get the same response: “The one who sang ‘Missing You?’” So sad, that someone would confuse me for the kind of person who fanaticizes over a one-hit wonder (and doubt not, sweet children, that these exist, for my sister has been dating, on and off, for years, a bohunk with a tour-following penchant for the singer of “Sunglasses at Night”). But I am not that kind. I am the kind who likes to mine the rich veins, the multi-album careers pit-stopped with soundtrack collaborations and ill-fated string arrangements. I swiped The Black Rider from my college radio station and liked it well enough, but when a temporary housemate played me The Early Years, Vol. 1, and I realized that all of this music was made by one and the same musician, I was hooked. Soon I was in such a swoon that I wrote smutty X-Files fan fiction named after (and prominently featuring) the titles “Please Call Me, Baby” and “Heartattack and Vine.”

So you see how my hard-on for truthfulness has persisted, to a point where it’s probably hurt me more than it’s helped. After all, this story may be read by hundreds of subscribers, and heaven can tell how many newsstand browsers and buyers. And now you all know my shame, that I once set Mulder and Krycek wrasslin’ to the strains of Mr. Waits. Not to mention that I wouldn’t be pulling poplar on an Indian summer day if it weren’t for the fact that I had to air my feelings about my fairly cushy newspaper job loudly and often enough to get myself unemployed.

But my honesty has served me well, too. In an effort to understand my compulsions, I’ve gone to therapy and studied astrology as means of getting to know, understand, and deal with my own strengths and weaknesses, abilities and liabilities; I have learned to look my talents and shortcomings in the face, using them or working all the way around them as the situation required. I’d once consulted a tarot-reading friend, who declared my “life card” the Chariot. Though the Chariot is often interpreted in the language of struggle, triumph and ambition, it also tells of “working within the boundaries of one’s life to build up a successful existence” (according to paranormality.com). I liked this. I looked at myself, at my 30-plus years, and saw an adaptability, a subtle control as I let events toss me from city to city, identity to identity, project to project.

Like Waits sang, “It was a train that took me away from here/ but a train can’t bring me home.” It was always a chariot that carried me to my destination, and I’ve never had much interest in treading over old ground, perhaps because chariots don’t easily retrace their bumpy tracks.

My chariot has also carried me from lover to lover, and that includes the one who used to cover “San Diego Serenade.”

“Never saw the white line, till I was leaving you behind/ Never knew I needed you till I was caught up in a bind,” he’d sing, and I’d swoon, resting the back of my hand on my forehead like a nickelodeon starlet, wristbones obscuring my vision so I’d miss the red flags. “Never spoke I love you till I cursed you in vain/ Never felt my heartstrings till I nearly went insane.” He’d been a neighbor of a friend, even dated her for a while; he’d stayed at my house for some weeks while trying to decide whether or not to move back to Chicago. One night in late 2003, I separated him from the small, wine-soaked party on my porch and took him to my room. Later, he went to the Midwest for the holidays, then came back to California to earn some money to move back out there. But when I heard he was staying with his ex up north, I bought him a bus ticket back to my city and my side.

I installed him in my house, where he cooked me soup and sang more softly the songs he’d holler for change in the BART station; sour and soulful, they imbued Waits’ broken-saucer-eyed romanticism with more anger, as if the mere suggestion of a string section would set his songwriting mind ablaze with fury. I helped him book gigs, paid the rent while he kept me warm all winterlong. Spring came, and I helped him do the paperwork to go work far away, in Antarctica, for five months.

At the end of his stint, we were supposed to travel together, something I knew next to nothing about. My chariot, as I’ve implied, takes me places; I keep it from veering off the road, but I know little about booking flights. Toward the end of his stay away, I began to bug him for plans—where would we go, for how long, etc. When he resisted these questions, I, somewhere down inside, finally began to tell myself the truth. So I got myself a promotion and a new living situation. I dug my chariot’s wheels in deep. And he returned, got depressed, told me he loved me but was confused, and within three months of returning had relocated to the Pacific Northwest to live under the roof of a girl he’d met while working far away.

Never saw the east coast till I move to the west

Never saw the moonlight till it shone off your

breast

Never saw your heart till someone tried to steal

it away

Never saw your tears till they rolled down your

face.

And oh how I cursed, and oh how I moaned. I had written in my journal, while he was living with me, about how office work was bourgeois, how I should learn a trade and be like my lover, sweat and break my back and make an honest living; I’d asked him to help me do this, and he’d nodded mutely and let me pay the bills. And then there I was, working my highest-paid, highest-profile-yet office job, and he had left me for a janitor girl he’d met down on the ice.

My big brother, concerned over my wounded heart but unclear on many of the concepts of my reality, sent an enthusiastically sympathetic bouquet to me at work, bearing a card that read: Don’t worry, you’ll find your Tom Waits someday.

But I cursed myself as much as I cursed my lover, for lying to myself again and again about what I’d expected, what I’d hoped for and what I should have seen coming a mile away.

And now I’m miles away; or, at least, months. It’s been a year and half since I got that last call from him. Back in Zoli’s garden, I looked over my left shoulder to the stereo system, catching a glimpse of the furrows I’d made around the fence, unraveling away from me like chariot tracks. I spent some time with my ex’s new ladyfriend this summer—in fact, it hurts me to call her a “janitor girl,” given that I like her (and that she may very well read this and, besides, now they both do office work down on the ice). Maybe I like her more than I like him, maybe not, though I know I trust him far, far less. I certainly trust her to keep her eyes open for red flags.

But I still don’t know what to do with the “W” shelf in my CD cabinet, don’t know if I should sell it off in one big swoop to save me the sight of my own fallibility. Because, to be far more honest with myself than I was back then, I don’t know when’s the last time I listened to any Waits, or when I’ll be able to again. I guess that, truly, Tom Waits didn’t ruin my life—my life ruined his music for me. And that’s a road I’d rather not have taken.

Stefanie Kalem is KS’ editor in chief and also its Sex, Food & God editor. She’s really gonna miss writing about her love life for this magazine.